Twitch live streaming events can be analysed from the perspective of production (Taylor, 2018) and spectatorship (Wulf et al., 2020). Taylor identified layers of production in a livestream, while Wulf et al tested four hypotheses around viewer enjoyment of livestreams.

I viewed three Twitch livestreams:

- Caseoh playing Fortnite

- Spacefrogs playing Journey

- HappyHappyGirl playing Fortnite

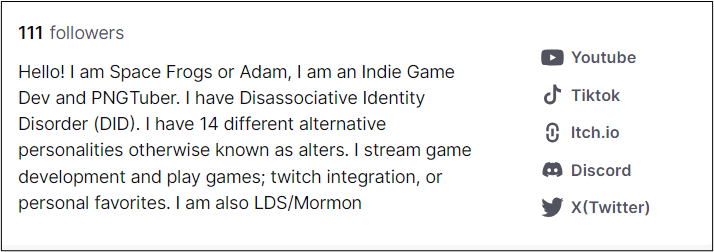

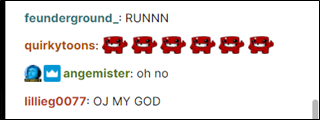

I selected streamers with different characteristics; gender and number of followers. Caseoh has 3.6M followers, followed by HappyHappyGirl with 119K, whle Spacefrogs has 114 followers. A hypothesis might be that accounts with large followers will concentrate on monetizing, while accounts with smaller followings concentrate on acquiring new subscribers.

Production

Set Design

“accomplished streamers often use complex ‘sets’” (Taylor, 2018, p.69-70)

The set designs in Caseoh and HappyHappyGirl’s streams shared commonalities: a talking head video overlaying the main game area and a chat window, but no additional graphics or avatars. An addition to the set design in Spacefrogs’ stream was a frog avatar that read aloud some of the chat contributions (Figure 1 bottom right). Another difference between Spacefrogs and Caseoh/HappyHappyGirl was the lack of a player video in Spacefrogs’ stream – instead they had an avatar (Figure 1 bottom left).

Performance

According to Taylor, successful live streamers “frequently use physical expressions and gestures, at times theatrically, accentuated, or held for effect, to punctuate their communication. This is typically accompanied with humor, frustration, and suspense.” (2018, p. 70)

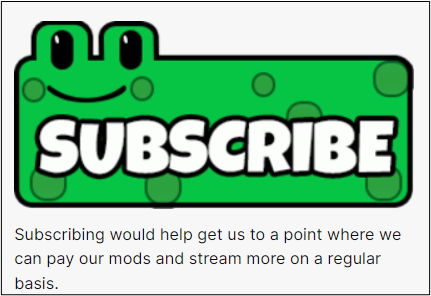

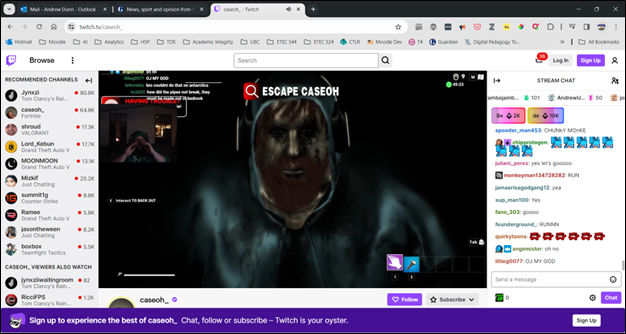

Caseoh and HappyHappyGirl both exemplified this. Caseoh used his voice and gestures to dramatic effect building tension as he played (Figure 2). HappyHappyGirl added unique elements to her performance; every so often she got out of the chair and did a dance! (Figure 3).

While Spacefrogs did ‘perform’, this was more low-key, and the lack of a video in the stream reduced the sense of performance.

Critique and Evaluation

“Astute streamers not only provide viewers with an entertaining performance of play but act as expert evaluators of systems too” (Taylor, 2018, p. 70)

Caseoh did not offer much critique or analysis during his stream. What critique and analysis there was came from the chat. For example a chat member told Caseoh that he should hide in recesses when he hears footsteps – a useful bit of gameplay analysis. Critique and analysis of the game was absent from the other two live streams, either from the player or from the chat.

Sociality

“Live streaming performance is deeply interwoven with audience and community engagement.” (Taylor, 2018, p. 70)

Sociality was a big part of the experience watching Caseoh. His engagement with the chat was constant – he was continually asking for chat advice on how to proceed, and to predict whether he would be successful.

HappyHappyGirl also interacted frequently with the chat and made a point of thanking new followers. She gave call outs to chat members and worked hard to reinforce the social aspect of the stream.

Spacefrogs had fewer chat members to interact with but made use of their bio to share personal biographical details as a way to create a ‘parasocial relationship’ (Wulf et al 2020) with followers (Figure 4).

Material and digital infrastructure

HappyHappyGirl demostrated the best production values in her video, while Caseoh seems to have deliberately chosen a low lighting level to create a mood. All three streams had decent quality audio. It was difficult to identify other material or digital infrastructure from watching the streams, but it was apparent that each streamer relied on additional support (e.g. from chat moderators).

Economic and commercial frameworks

Streamers with the largest audience included monetization features in their streams. Caseoh, for example, included a popup indicating that a follower had donated. His channel also had tie-ins with online retailers (see Figure 5).

HappyHappyGirl monetized her stream using retail tie-ins (Figure 6) and by having full screen ads in the main game area.

For Spacefrogs, much of the content on the main page was designed to drive subscriptions (Figure 7). There was a button for tips, but unlike Caseoh’s and HappyHappyGirl’s streams, there was no tie-in with online retailers. Monetization did happen during the stream, with ads appearing intermittently.

Spectatorship

Wulf et al (2020) hypothesised elements that promote spectator enjoyment. These were exemplified by Caseoh’s stream. In particular their hypothesis that chat positively contributes to enjoyment was supported. The chat was busy, and much of the enjoyment came from watching how Caseoh interacted with it. Likewise, the hypotheses relating to the contribution of states of suspense to enjoyment was also exemplified by Caseoh’s stream. Using physicality and dramatic voice, Caseoh contributed to the suspense in the game (Figure 8).

Their suggestion that players and spectators exist in something like a parasocial relationship was supported by Caseoh’s stream. Caseoh played the same level 4 times while I viewed. I could see the relationship between the gamer and the chat participants, all of whom were rooting for him to succeed (Figure 9).

The experience of watching HappyHappyGirl was similar to that of watching Caseoh. Both employed humour and dramatic video to create a link with their audience in the chat. At one point, HappyHappyGirl was killed in the game and was quite apologetic to the livestream viewers, indicating that she saw them as being invested in her gameplay.

Journey has much less dramatic tension than Fortnite, and this was reflected in the spectator experience of watching Spacefrogs. They did interact with the chat, but there wasn’t the same level of intensity as with Caseoh or HappyHappyGirl. Spacefrogs didn’t elicit advice from the chat, for example.

It’s not clear whether the characteristics of Spacefrogs’ stream were because of the small number of followers, or whether there were fewer followers because of the experience, which was less engaging and entertaining than Caseoh or HappyHappyGirl.

Summary

It seems that the economic and commercial framework described by Taylor (2018) is more prevalent in streams with large numbers of followers. Sociality (interaction with the chat) was a common theme across all the streams I watched, supporting the conclusions of Wolf et al that social interaction is a key element in spectator enjoyment of a twitch stream.

References

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Twitch and the work of play. American Journal of Play, 11(1), 65-84.

Wulf, T., Schneider, F. M., & Beckert, S. (2020). Watching players: An exploration of media enjoyment on twitch. Games and Culture, 15(3), 328-346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412018788161